mittmattmutt's blog

Radical Publishing: A Proposal

The aim of this post is to present a way of producing and consuming literature, one radically different to the prevailing and flawed model. It’s roughly inspired by the radical markets movement and theory I talked about in this post, and one which I think could dramatically improve the experience of both readers and writers, both in terms of fairness and quality. First I’ll present the prevailing model, then sketch my alternative, then flesh it out by considering some objections.

The Traditional Model

It helps to understand how literature is produced and consumed by considering a simple model of it. Call the traditional model the following. At heart, there is a set of authors *who produce what they take to be good *novels. A novel takes a long time to make and costs, comparatively, a large amount. There is a set of readers who buy what they take to be good novels. Some people agree about what makes a novel good, but there is great disagreement and no consensus.

In between readers and writers, there are the people who determine what to publish, physically produce it, and promote it. Call these people filterers, because their main purpose is to act as a filter which stops bad work and lets through the good work deserving of our attention. Literary agents, who deal with publishers on behalf of authors, editors at publishers, reviewers, editors of book pages in literary magazines, owners and deciders of various literary prizes are all filterers.

The current system doesn’t work well for many. The vast majority of authors, many of whom have dedicated years to their craft, never make it through the filtering stage, and remain unpublished and unknown. And my suspicion is that many readers are not well-served by the filtering process in the sense that it doesn’t yield reliable recommendations about what books are good. I at least used to buy the books praised by the filtering system to discard them after 50 pages. And I find books I love almost always by recommendations from people who know literature, or even purely by accident. The most astounding book I read in 2017, Michael Muhammed Knight’s Impossible Man, I found because I was reading in a quiet section of a library and the book beside it had a shiny cover that made me go look. I so easily could have been deprived that great reading experience, and that makes me think about how many great reading experiences I and others are deprived of by inadequate filtering. We should fix that.

Moreover, the filtering stage is often seen to be inept and/or corrupt. Publishers (thus agents) are apparently very poor at predicting when a book will do well, but since that’s pretty much their whole job, that isn’t great. Reviewers often review their friends gushingly (see the UK satirical magazine Private Eye’s recurring section ‘log rolling’ which details this); and prizes are often functions of money and promotion (looking at you, Man Booker Prize).

(A diagram would be nice here. I lack the skills to draw a nice one, so imagine: on the left of the page, a swarm of dots of many colours, the authors. Colours represent taste/perspective. Lines connect elements of the swarm to a homogeneous grey blob in the centre of the page, the filterers. The grey blob is then connected by lines to another swam of coloured dots on the right, the readers. While this is a bit of a tendentious use of colouring, where’s the rule that says imaginary diagrams can’t be tendentiously coloured?)

Note that the traditional model is arguably not all bad. It makes sense under the assumptions of a relatively small number of writers and a relatively homogeneous-in-taste set of readers. In such a case, provided the filterers’ tastes coincided with the tastes of the readers, good results would follow. Arguably, this would have been so 100 years ago and perhaps sooner, when in particular access to intellectual life was much more restricted. If primarily white middle-class men were writing for white middle-class men readers, then white middle-class men filterers wouldn’t cause too much damage.

But things have changed. Increased access to in particular tertiary education which, at least in the humanities, teaches one, if nothing else, how to regularly put decentish number of words to paper has meant that being a writer is something which many now can quasi-reasonably aspire to. For at least the same reason, readers have got more diverse. Moreover, technology has changed: thanks to e-readers and print on demand, publishers qua people who actually produce a book are no longer needed. Thanks to technology to monitor and pay for microactivities — reading a page and automatically paying for it, say — we need no longer be shackled to the book — expensive to create, buy, and read — as the unit of literary production, and can instead hone in on the chapter or the page, so that the unit of literature more closely reflects how we consume it (a page at a time, preferably with an option to stop reading if we get bored).

That circumstances have changed suggests to me that our model should change. Given we have many more writers, we should try to put as much of their talent to use. Given we have many more readers occupying different perspectives, we should try to find a way to connect them to works they, they in particular, will actually like.

An Alternative

Here is my suggestion for what an updated model could look like: firstly, more writers would be involved, and we would do that by making mainstream the process of — perhaps massive — coauthorship of literature. Coauthorship works very well for television; if you balk at the suggestion that literature should be coauthored (as you might — would one really want to tell Beckett, Dickinson, Kafka, that they should have coauthored?), I reply that you need to broaden your horizons. Literature has no essence, and I’m not suggesting that single authorship cease; we should just make literature more, by expanding its scope to better use the talent available to us. Nevertheless this is a solid objection that I respond to in more detail more.

Secondly, much of the apparatus of the filtering stage — agents, publishers, and reviewers — would cease to exist, and be replaced with a way of connecting writers and readers that works: that hooks up readers with books they will love. Basically we introduce a recommendation market: we take the money used for filterers and pay individuals (which crucially and plausibly will contain underemployed writers) who successfully connect readers to books they love, using a standard knowledge-revealing market mechanism, and, crucially, bringing people en masse into the process of disseminating and recommending literature, rather than it just falling to a few elite reviewers, agents, etc. Think of it as a peer-to-peer model connecting writers and readers, with only a sliver of a middle man in the recommender, whose work we can rely on because it is paid (in imaginary diagram terms: the middle grey blob is replaced by another coloured swarm, into which and out of which the lines come.)

Thirdly, we take advantage of technology and introduce a pay-by-page model. You only read what you pay for so that payment is proportional to the time spent reading (in the current model, if you buy a book and give up after 50 pages, you don’t get a refund.) This model is much fairer, and will enable readers to try out many more writers until they find one they like, and will thereby increase the number of writers being read.

I think this is a really interesting model, one which promises to make things both better and fairer for readers and writers alike. I take it that points two and three, while novel, are understandably so. Hopefully you can see the logic and why such things might be desirable. In this brief post, I won’t say any more about them. However, the first point, about coauthorship, might seem very undesirable, and so I will spent some time defending the idea. I should say, though, this post is really a first word, a beginning tentative look at an underexplored region of logical space, and — hopefully obviously — not final thoughts.

(A note: while I’m calling for the abolition of filterers, filterers shouldn’t be that worried. I myself am a filterer (albeit in academia) and the important thing to realize is that while I propose to eliminate jobs, I also propose to create new jobs which could be occupied by the current filterers. My aim is to get rid of the poorly designed institutions of filtering; the talents filterers have will still be needed. Also, let me take this parenthesis to shout out the people who are already doing good work in this area. I think in particular of indie publishers Dostoyevsky Wannabe who by dint of talent and clever use of technology punch much above their weight and deserve a lot of admiration.)

Potential Problems For Collective Authorship

Collective authorship has at least the following advantages: it would give people whose work is now completely ignored the chance to make some contribution to works people read. Many more voices will be heard (albeit, heard for less long than if they managed to get a novel released), which I think is inherently good. And people could begin to make reputations for themselves by amassing small contributions. The more fine-grained feedback mechanisms technology gives us (such as, for example, seeing how many people lingered over a paragraph or highlighted it) could, moreover, enable such writers to see the effect their work is having on people.

Less substantially but almost as importantly, it would foster a spirit of collaboration rather than the current model, which promotes competition between each other, vying for position, kissing the ass of filterers and successful people, and so on. A model of literature on which others’ success is in part your success — on which you can whole-heartedly enjoy another’s contribution because you’re contributing to the same thing — is also, I think, inherently desirable.

Finally, and potentially most importantly, but most uncertainly, it could dramatically improve literature itself. If something like a wisdom of crowds phenomenon holds for literature, then we could see new works, much more varied and wide-ranging than any one person could manage. New mega-works of a quality we can barely yet comprehend. That’s an exciting possibility.

When you combine this with my idea of having people act as paid recommenders — a job writers would be very well suited to — the proposal offered here should seem attractive to many writers. But one might also have some worries about it. I address a couple below, taking the opportunity to flesh the view out a bit more while doing so.

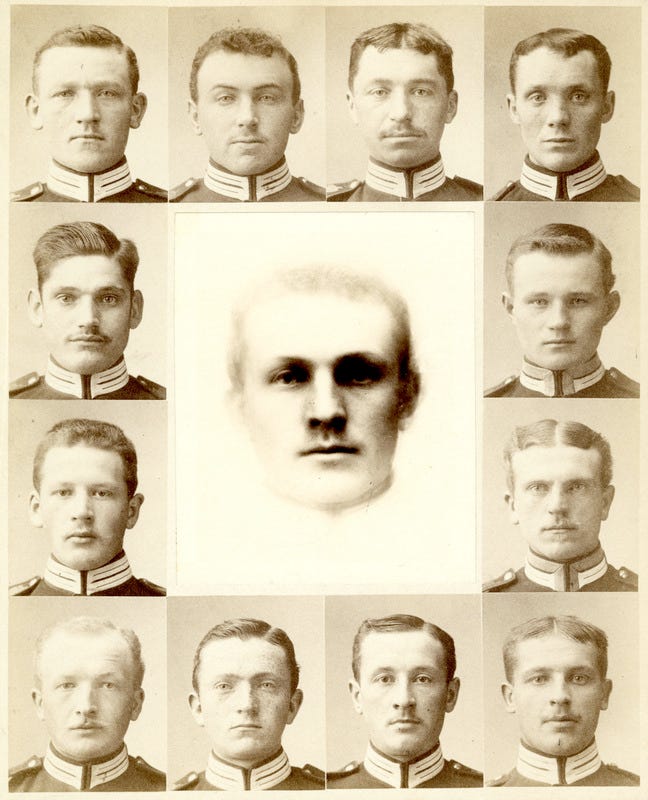

One might worry that collaborative writing will lead to undistinctive work, as

superimposing photos of faces leads to blurry indistinct faces. This isn’t so,

though.

One might worry that collaborative writing will lead to undistinctive work, as

superimposing photos of faces leads to blurry indistinct faces. This isn’t so,

though.

Bad For Literature?

Let me focus on the objection I raised above: that coauthorship is inimical to literature. Literature, one might think, is the expression of one’s very particular perspective on the world; any attempt to combine perspectives will lead, like Galton’s composite photographs, to unsharp blurry distortions. Again, think of the greats of literature. We like Beckett because his world is so different (and yet so familiar) to ours: so weird, so particular, yet understandable. If we were to miss out on voices like that, that would be very bad.

More generally, we have this idea that creativity doesn’t work with groups. (What is that saying? A zebra is a horse concocted by a focus group? I genuinely can’t remember and google isn’t helping. It’s some witticism about how focus groups brainstorming lead to silly things. If you know the quotation I’m thinking about let me know.) And you, as a writer, let’s say, may look on the proposal with horror: you want to tell your story. The thought of letting anyone else partly tell it is deeply unattractive (mentioning this idea to a couple of other writers, this was the response I got).

I realize the force of these considerations but ultimately I don’t think they work. The basic reason for this is that I’m not suggesting that all literature be cowritten. I’m suggesting we expand our conception of literature so as to countenance in addition to singly written works coauthored works as mainstream productions. (I’m aware that coauthorship at present exists (such as the Wu Ming collective). As far as I know, however, it’s somewhat fringe).

We know that coauthorship works in other disciplines. Speaking personally, some of the art I hold most dear — The Simpsons and Seinfeld, for example — are coauthored. Moreover, and interestingly, these show that coauthorship doesn’t even imply the dulling of a distinctive narrative voice. You can tell a John Swartzwelder episode of The Simpsons, or a Larry David Seinfeld (at least, if you’re a massive nerd like me who has watched each episode upwards of ten times) very quickly. It has a distinct feel and vibe, and yet — as far as I know — it, like every other episode, would have been subject to rewrites by a room full of writers. This suggests for the cynic a possible way to start exploring this idea: look at how writers’ rooms work, and try to make, so to speak, prestige literature, a sort of group-written literature explicitly modelled on prestige TV (if you’re snobby about TV, you probably won’t like this whole idea; fair enough, you should probably stop reading.)

But even more basically, I have to accept that maybe it won’t work. Maybe for some weird reason coauthored literature doesn’t work. The thing to do, I think, is try it out under the right circumstances and see. It would be an experiment, but one with a great possible upside — promise to use much of the unused creative labour in the writing community — and so an experiment worth carrying out.

Bad For Writers?

But, wait, you might think. Would this really be good for writers? If a motivation for writing is simply to put one’s perspective out on the world and be recognized for it, you might not be happy contributing a few pages or plot ideas, nor content with your name just being one among many. You want fame!

A couple of responses: we can’t all be famous. Under the normal model, statistically speaking you’re likely to make no contribution to the art of the world, and thus to receive no recognition. The alternative I’m proposing is that you could instead to try to make a small contribution and receive a small recognition. Whether you try that is entirely up to you: to repeat, you’ll still be free to single-author things. It’s just a question of working out what your values are. A small shot at big fame or a decent shot at small fame. I’m adding to, not removing from, artistic possibilities.

And anyway, secondly, it’s not the case that being part of a writing team condemns one to obscurity. Comedy nerds follow the careers of our famous writers. We watch The Good Place because Megan Amram writes for it, and she was one of the main voices on Parks and Rec. Conan O’Brien got his start as a Simpsons writer. Examples could be multiplied. While these are exceptions and most TV writers aren’t so famous, equally most people who write aren’t as famous as the people you read about in newspaper book sections.

Bad for readers?

But … what is the goal of collectively written fiction? The goal of single author fiction is, you might think, to give voice to your perspective. In the absence of a single voice, is there not a risk that this idea will produce cookie-cutter mass produced fiction? That, in trying thus to satisfy everyone, you will satisfy no one?

Let me answer these questions in turn. First, the goal: I can remain agnostic about that. The goal of collectively written fiction is the same as the goal of The Simpsons writers: good art, whatever that means.

(Not being agnostic opens up some interesting possibilities given the framework I’ve posited. If we’re adopting a micro-work micro-payment model, where authors just pay for what they read, then we could fine-grain the concept of good fiction in terms of what keeps readers reading. We could even do things like A/B test different plot points. But I won’t elaborate on these very suggestive ideas here.)

As to the cookie-cutter point. There’s no logical reason why a plurality of voices implies blandness. At the risk of repetition: The Simpsons. More generally, we can use data to build up fine-grained target audiences. And we can then have a collective attempt to write, say, for the lovers of postmodern American avantgarde fiction. Such a collective, presumably, will consist in postmodern American avantgarde fiction writers producing postmodern American avantgarde fiction. The point is, blandness only follows if you treat the audience as a homogeneous entity: one size fits all. But that isn’t the suggestion, which is that we divide the audience up into many different audiences with different tastes which we can then target.

There’s more to say. I encourage you to think of objections I haven’t considered or benefits I haven’t mentioned. It’s a massively unexplored region of logical space that we should try to explore.

Let’s say you like some of these ideas. You might think nevertheless they are unimplementable. One important thing to note is that plausibly there are people out there who would benefit from it, and who thus might be willing to try it (all you need to assume is that you can map every published writer of a given talent level to an unpublished writer of the same talent level (very plausible) and every reader well served by the traditional filtering model to one poorly served (again, pretty plausible, I think), and that there are a range of people who would, in exchange for money, try to connect readers and writers (again, pretty plausible), and you have the numbers). Implementing such large scale institutional changes are difficult, I grant, but that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try.

Society has changed but the institutions of literature haven’t changed with it. They should change. I have begun here to suggest a way they could change. Even if you don’t like my particular suggestions, I hope you see the value and indeed the necessity of this project.