mittmattmutt's blog

What Is Distinctive About the 2010s?

19th century German philosophers spoke of the the Zeitgeist, or spirit of the times. This is perhaps an idea most commonly associated with Hegel, who viewed history as the unfolding and development of the human spirit, which manifested itself in politics, art, philosophy, and so on.

But even without considering that somewhat lofty theory, the idea of a Zeitgeist is something we seem to recognize. We speak of the swinging 60s or the roaring 20s, for example. We think of the end of the 20th century as cynical and disaffected (Gen-X), mid-20th century Paris as broodily existential, the turn of the 20th century as gilded. Examples could be multiplied, but in each case there seems to be a dominant feeling or concept that we use to sum up an era.

What, looking back on today from the future, will we say the spirit of our era is? Is there a prevailing mood or concept that captures it, as some sort of freedom and rebellion might characterize the 60s, cynicism the 90s, and so on?

You might think this is a bullshit question. A respectable response would be to say that our Zeitgeist is characterized by the recognition that Zeitgeists don’t make any sense, because there is never only one spirit of the age.To take just one example, to speak of the swinging 60s is to make a mockery of the fact this was a decade when racial segregation was still widespread, when marital rape wasn’t recognized, when gay people were discriminated against, and so on. Perhaps we recognize better today that any society is characterized by a plurality of a perspectives and that to pinpoint just one as definitive of a time is at best offensive and at worst useless.

Maybe. I’m kind of sympathetic to this response. But, just as a matter of fact, when thinking about this question it seemed to me that an answer suggested itself that I found kind of compelling. So I’ll give it anyway, and you can decide if the answer is of any use in understanding today, the worry of the last paragraph notwithstanding.

So let’s grant that this is at least possibly an interesting question to ask. A next question is: well, how should we answer it? How do you find out what is distinctive of an age?

An initially attractive thought might be (to put it a little facetiously): take all the think-pieces, make a word cloud of them, and see which word is biggest. We would see things like: Trump, #metoo, social media, neoliberalism, big data, climate change, and so on. Maybe the spirit of the age is the biggest word, or some concatenation of the biggest words, or some summary of what they all have in common.

This would be useful. But I think it would miss something important: it couldn’t be guaranteed to give us what distinguishes a particular era from others: that marks that era out as different from the rest. Moreover, we’re really looking for patterns, not just particular instances. As to the first point: neoliberalism isn’t uniquely definitive of the 2010s. It goes back at least four decades. As to the second: merely listing Trump doesn’t give us the tool to understand the age. Trump is a symptom, not a cause, one might think.

So I think a mere list of hot topics isn’t enough. We want to find the distinctiveness our era; what differentiates it from other eras. That means that our approach should be comparative. So here’s a thought: compare our time with other times, and look for the differences. To try and pin down the distinguishing cultural features of a particular time one should consider different times. Below, I’ll try to begin to do this.

It’s hard to know where to start, so let’s just pick a nice round number. Let’s go back one hundred years, to 1919, see how things were then, and then try to see if any interesting differences present themselves. I think they do. (I carried out this project at much more length in my book Before The Internet, where I compared today with the 90s. A link to a draft of that book is in my bio.)

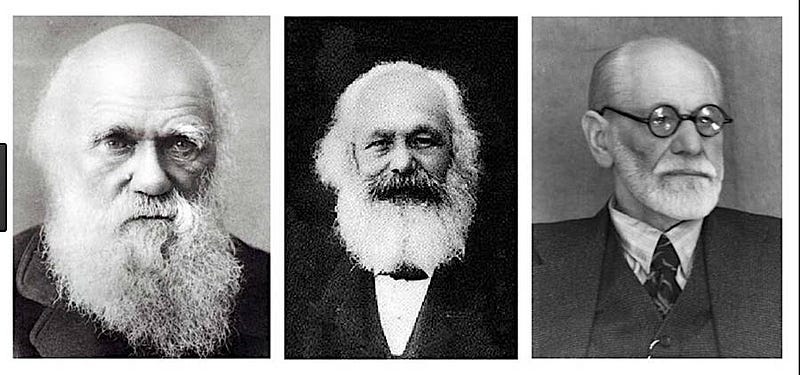

So what would the Zeitgeist of the 1910s look like? Here’s a suggestion: it would be one largely determined by of Freudianism, Darwinism, and Marxism. The key shared feature of these three theories is that they make worlds — mental worlds, natural worlds, social worlds — intelligible. And in making them intelligible, at least in some instances, it makes them controllable.

I will suggest that as intelligibility and control were arguably a key feature of the Zeitgeist one hundred years ago, so unintelligibility and lack of control are key features of the 2010s Zeitgeist.

Instead of Freudianism, which postulates meaning everywhere, we have AI and psychiatry as guiding our conceptions of mindedness, which locate mental disorder in brain chemistry disorder without saying why that particular brain chemistry disorder explains sadness or anxiety or paranoia, and which understands intelligence as crunching as much data as many ways as possible to yield predictions beyond what human minds could get at.

Instead of the Marxist classless future in the hands of the many, we are looking down the barrel of climate change which we seem powerless to control. And instead of Darwinism explaining everything, we have fragmenting siloed academia, replication scandals, hoaxes, post-truth and all the rest.

Altogether, we have a Zeitgeist, I suggest, typified by unintelligibility and a consequent powerlessness. That’s pretty depressing. But that’s not really my aim. Instead, I hope that by making these perhaps latent features of how medicine, technology, politics etc. shape our worldview, we can correct for them and, understanding what our age is like, better understand how to make it better. Below, I provide very brief primers on the theories mentioned above to try to substantiate my claim.

Darwin, Marx and Freud were responsible for much of the Zeitgeist of 1919, I

claim.

Darwin, Marx and Freud were responsible for much of the Zeitgeist of 1919, I

claim.

1919: Superfluities Of Meaning

I take it that a key feature of the three -isms I considered is that they offer explanations where explanations previously were lacking. Marx argued history wasn’t just one damn thing after another, but an ordered working out of class struggle. And Freudianism and Darwinism are the same, if in a sense almost mirror images. For Freud, even seemingly purposeless, marginal, accidental behaviour could be explained as, in a sense, intentional, while for Darwin, puzzlingly seemingly purposeful and adapted behaviour and organisms could be explained without positing some intentional agent responsible for them. In each case, we get explanations, and with them, the chance to control things. To resolve our mental sufferings by attending to dreams; to resolve socio-economic inequality by waiting until the capitalists dig their own graves (I’m not sure if there’s a neat ‘to resolve etc’ thing to say about Darwinism, so I won’t reach for one).

In slightly more detail, take one of the most famous and intuitive examples of natural selection in action, the increase in the number of black peppered moths before and after the industrial revolution. Read the wikipedia for more information (I’m getting all my info most proximally from it) but at the start of the 1800s, there were very few black-winged moths: most were whitish. Then the industrial revolution and air pollution came along, and the world was bathed in black soot. Against blackened tree branches white moths stood out and were eaten. Black moths did much better, blending in. And so, even if there were few such moths to begin with, being less likely to be eaten, they were more likely to reproduce and yield black moth offspring, and so on. By the end of the century, black moths outnumbered white ones.

Before Darwin, this is entirely baffling: how on earth did moths learn how to change their wing colour so as to better camouflage themselves? But about twenty years before 1919 — again I’m getting this straight from wikipedia — someone put it forward as a convincing vindication of Darwin’s theory. It’s thus highly likely that it’s the sort of thing that we’d be reading about in articles shared on twitter and the like, and the sort of thing that would inform our 1919 person’s worldview.

Sort of similar, sort of opposite, things hold for the Freudian theory. Perhaps Freud’s most famous work, the Interpretation of Dreams, was again about twenty years old at that time (bear in mind information was propagated much slower back then, so twenty years is probably much more time now than it was then). In it, he claimed to have come up with a way of explaining and curing what we would call mental illness.

His main idea, I take it, is that everything has meaning; everything we do fits in to an explanation of what’s going on with us. In his early works, he was interested in — in addition to dreams — slips of the tongue, misrememberings, jokes, and in general phenomena that most then (indeed now) would tend to have marginalized as belonging to the unintentional, as not worthy of serious attention.

Freud disagreed. You could learn a lot about a person from their dreams, their jokes, what they forgot. That’s because, although these phenomena appear to be meaningless or ungoverned by rules, really they are just obeying a different set of rules about meaningfulness, namely the rules of what he initially called the unconscious.

Living in society our desires are constantly thwarted. But in being thwarted they don’t just disappear. They get repressed, put out of consciousness, so that we don’t even realize we even have the desires in question any more. But this repression only kinda works, and it only kinda works because the unconscious has a way to communicate, via these marginal phenomena, and it does so. If you really look closely at the marginalized features of a person’s behaviour, you will see the unconscious speak.

Freud’s theory, especially its later and more famous Baroque taxonomization of the mind into ego/superego/id or again its obsessive reliance on Oedipus complexes, hasn’t really — as far as I know, which isn’t too far — held up. But that doesn’t matter: its failings wouldn’t have been apparent, I claim, to our denizen of 1919, and so, again, they would look out not only to the weird features of nature and find explanations, but could look into their private and bizarre moments and even find order and intelligibility, and the promise of respite from suffering, there.

Our third -ism is Marxism. The dates aren’t quite so great here, the Communist Manifesto being 1848, and Kapital being 1867. But the theory would surely have been high in people’s minds in light of the October revolution of 1917 and other similar revolutions and strikes that happened around then. Had a Marxist state been established in 2016 or 17 we would probably have been paying attention that theory.

And again it’s a theory that promises to offer order, explanation, and control. As the capitalist class increases, as it had so notoriously been doing in the 70-odd years our 1919 person would have looked back on, so must its source of labour increase. As businesses get more organized, so, in a sort of mirror image, do workers. As factories spring up to make things more efficiently, masses of people are brought together to make them. As business owners try to maximize profit, they try to squeeze over last ounce of work from their workers. These united, downtrodden workers eventually say enough is enough, revolt, and break down the capitalist-worker opposition.

The progress of capitalism means the increasing association of workers, who will eventually realize capitalism isn’t such a good deal for them, and will then revolt. Capitalism’s very success implies its failure. This would have seemed pretty plausible in1919, abubble as it was revolutions and such (in Italy, in Russia, in many other places).

Again, the point is that we have the promise of explanation and control. It was a theory that both offered to explain the past (history is the history of class struggle) and the future (eventually the working class will win this struggle). And so, one could forgive the 1919 observer for thinking here, at the world-historical socio-political level, the world was also understandable.

2019: Unintelligibility

And what about today? I propose to try to answer this question by focusing on the domains of the three theories, somewhat roughly construed, and seeing how things have developed. Consider first the mind, minded behaviour, and mental pathology. How do we think of them today?

Two things come quickly to mind: psychiatry, and in particular the model of mental illness according to which it is question of a bit of the brain not working correctly, and looming AI. According to the former (for which see, for example, this and this) mental illness results from malfunctioning brain chemistry. I won’t go into the details — you can follow the links, or read the books mentioned in the links (the story of the development of psychiatry in the second half of the twentieth century is fascinating) — but the key point is how much it strips of meaning such an important feature of human behaviour. We are told that depression is a result of poor serotonin uptake, but we are not told why and how that connects to depressed behaviour. Why is it that the many and baffling symptoms of depression are down to this bit of the brain?

Well, maybe this just isn’t a question one can or even ought to try to answer. Maybe that’s just how things are. But even if this is so, it still leaves us with a notably different self-understanding, one that feeds in to my theory of our Zeitgeist. For the Freudian, mental suffering, in all its wide and bewildering varieties, is a very human thing. It’s because we don’t get what we want. That makes sense. For us today, it’s a biological thing. These are different.

As to AI — I take it that a key feature of the contemporary big data-fed artificial intelligences — the ones that make sudden leaps forward, that predict illness better than doctors, that are biased against black people — is that they can’t show their work — they can’t explain to us how they spit out the answers that they did spit out, because they did so by crunching a vast amount of data a vast number of ways. That’s their point, I take it — to find patterns our puny human brains can’t latch on to. But if that becomes our paradigm for intelligent behaviour; if such algorithms replace our doctors and bureaucrats, then our world will be one whose operation is increasingly opaque and unintelligible to us. And I think this feeds into how we understand the world, and how others will explain in the future how we understood the world.

Consider now the world on a larger scale. On the Marxist theory, history was heading somewhere in accordance with rules, and moreover very attractive rules that brought people to rise up against the forces that oppressed them, in order to make a better world for us all (well, apart from the exploitative bourgeoisie, but who cares about them?) What about us today? We’re arguably at the tail-end of a failed economic paradigm and looking for a new one, and although there are suggestions out there, there isn’t any one that captures all our imaginations.

But also, and I think more importantly, there does seem to be a future we can see: it is one of automation and climate change. Consider just the latter: each month, it seems, we read new and dire predictions about global warming, but it also seems — this sounds kind of defeatist, I hope I’m wrong — that there is not much to be done. A small number of companies are mostly responsible, and there is no neat Marxist logic to show us how the millions of people who will be affected by climate change are to fight against them and get them to change their ways. We look on the future with impotence.

Finally science, and academia more generally, is also in a less great place than 100 years ago, when we had, in addition to Darwin triumphant, the stunning empirical verification of Einstein’s theory of general relativity (for which you could start here). Now what do we have? Replicability crises, hoaxes, adjunctification, self-serving scepticism towards experts, counterproductive measures like the REF, and worse (‘fake new’, ‘alternative facts’, ‘post truth’, etc.) We have less confidence in science, that great source of explanations about the world.

In sum, taking it all together, I think a reasonable case is to be made that a distinguishing feature of our era when compared to 1919 is that intelligibility has been replaced by unintelligibility, and control by lack of control. Where before we could wait for history to unfold, could understood the order in nature, could solve our mental woes with analysis, now we face the blackboxes of brain chemistry and neural networks, untrustable science, and a planet being warmed by a small group of people whose behaviour we can’t control.

That’s a bummerish note to end on . But, as I said above, my aim wasn’t really to be negative. Rather, it was to present a way to better understand our current situation and how we view the world, in the hope that, understanding those things better, we’ll better be able to deal with them and fix the various problems we face.